In November-December 2021, the Dutch National Program Open Science (NPOS) set up an open consultation (archived link) to give all Dutch stakeholders the opportunity to provide input on the NPOS2030 Ambition Document, comprised of NPOS’ vision for 2030, the guiding principles underlying this vision, and the proposed program framework and key action lines.

Here we share our submitted response to the consultation. The response was drafted in collaboration and submitted on 2021-12-22.

Jeroen Bosman ![]() (@jeroenbosman)

(@jeroenbosman)

Bianca Kramer ![]() (@MsPhelps)

(@MsPhelps)

Jeroen Sondervan ![]() (@jeroenson)

(@jeroenson)

Part 1: NPOS Guiding Principles

General remarks:

- The document lacks a sense of urgency. Apart from the Citizen Science aspect it is not sufficiently clear in what ways this ambition document adds to or deviates from the previous NPOS programme. We also miss reflection on the previous programme. Has that been successful in all respects and if not, how does the current ambition address that? Will those acting in this space (esp. on open access and FAIR data) do anything differently because of this ambition? Will they feel inspired or supported by guidance offered in the abition?

- We are somewhat disappointed by the relatively narrow scope of the ambition and by the lack of concrete proposals to make real steps forward in practising open science. Especially so, because this should be an ambition for the next 8 years. A period in which it is expected to see lots of developments in different aspects regarding Open Science.

Just a few suggestions of the type of actions and goals that we miss:- in open science in education: embed the open science skill set and mindset in all bachelor and master programmes at universities and universities of applied sciences;

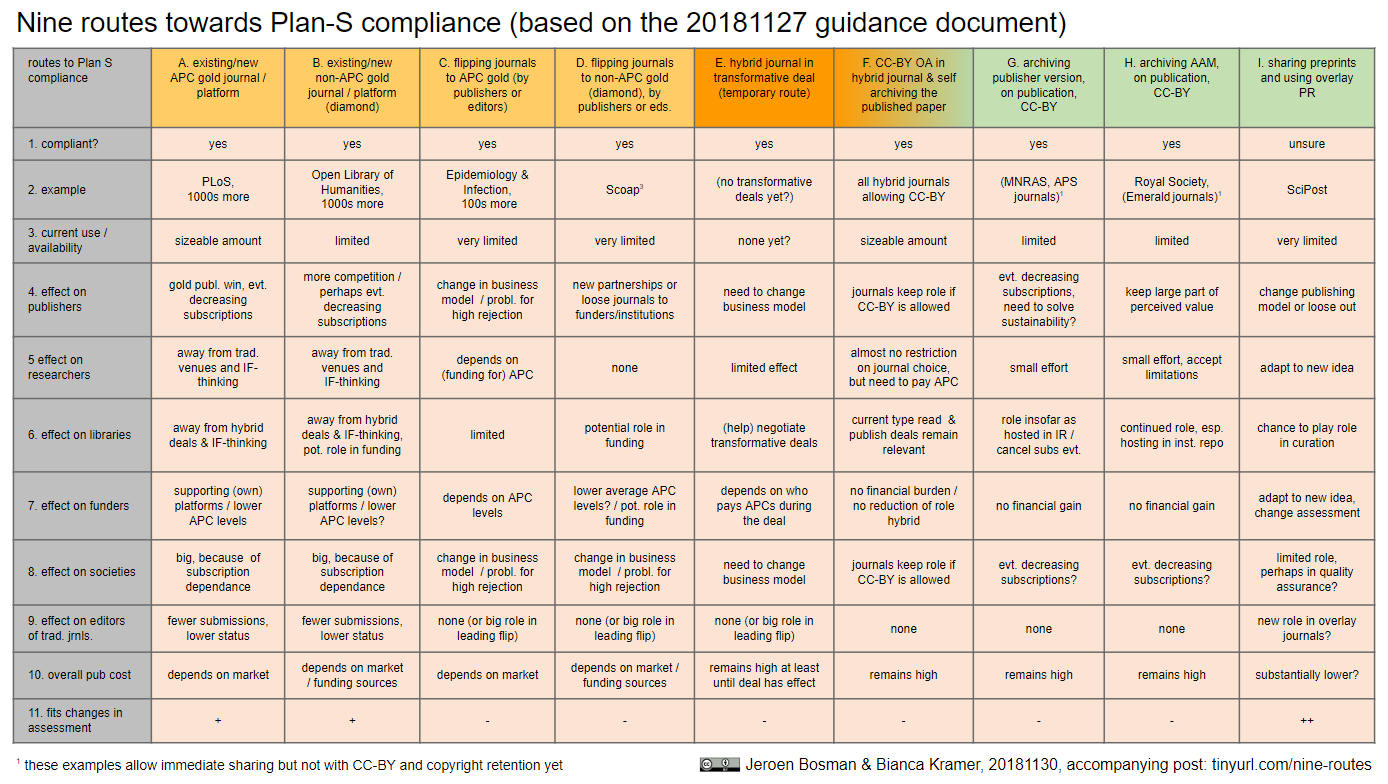

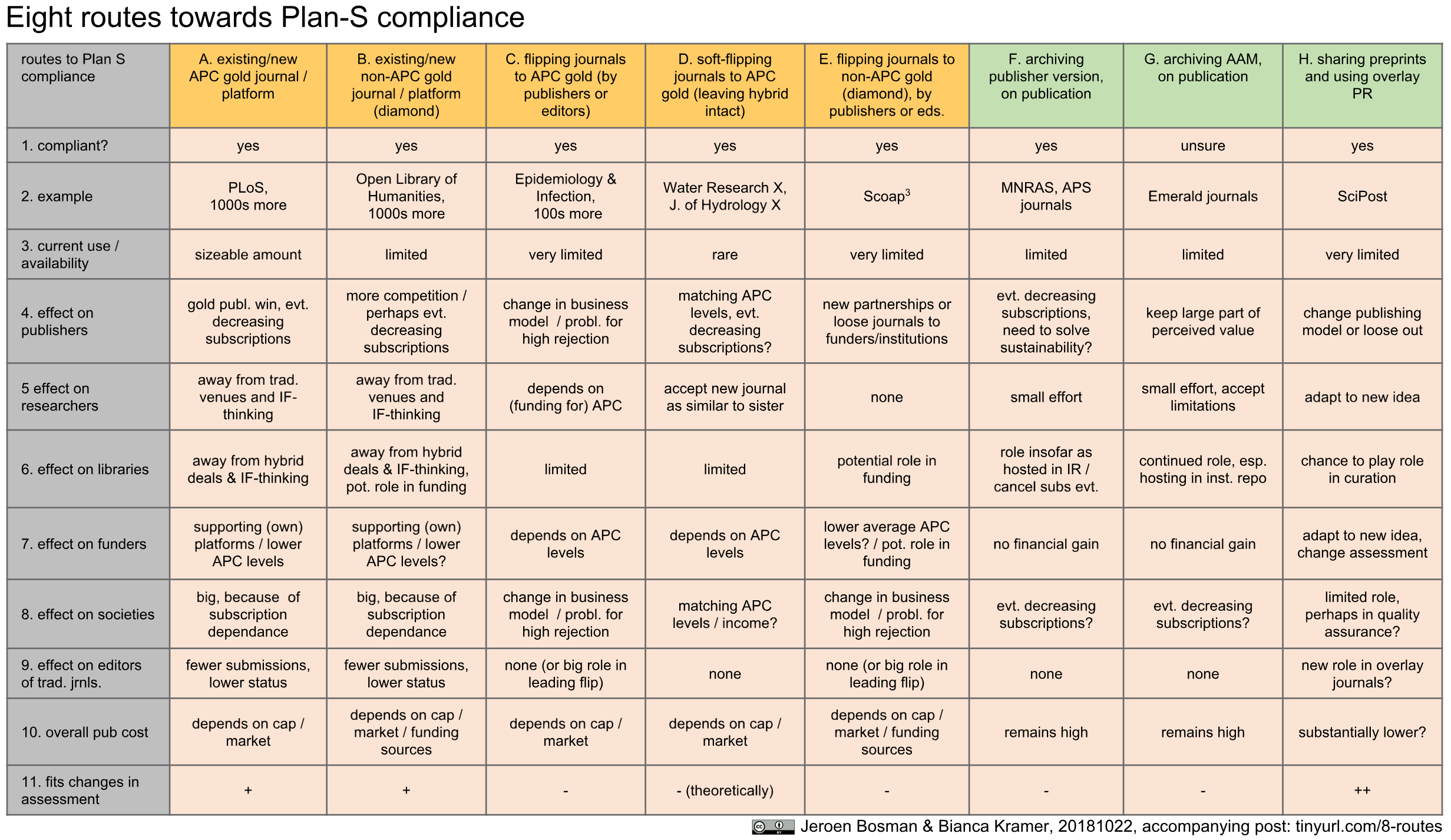

- in open access: move towards 50% diamond article publishing by 2027 and create a national open source and publicly governed ORE type publication platform;

- also in open access: create a national campaign to deposit all retrospective output of current affiliated researchers using Taverne;

- in rewards & recognition: foster a culture in which journal/publisher level evaluation of publications/researchers is no longer desired;

- in public engagement: create support to help researchers to add plain language summaries to all their publications and deposit those with the articles in repositories and also create infrastructure to leverage those summaries in public engagement

- also in public engagement: explicitly reward researchers for using 1% of their research time to check and improve wikipedia on their topics

- Overall the structure of the entire document could be better and we suggest shortening of the document. Parts of chapter 1 (especially section 1.3) could be integrated in the following chapters 2, 3 and 4. As a reader it is confusing to first read quite elaborately about these topics and then see them detailed even more in separate chapters. We suggest to integrate 1.3 into the three following chapters, thus dealing with the vision, mission and action lines in a coherent way in one place for each of the three domains.

- The structure of Chapter 1 is unbalanced. It begins with the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science, But on further reading, this definition seems to keep standing on its own. Throughout the document, little or no connections are made with the recommendation and to what extent the NPOS adopts this definition in full. By making this more clear and more importantly justify the choices being made that are guided by the UNESCO Recommendation, it would make the NPOS statement much stronger and ‘embedded’. By doing so, it is probably also much easier to connect principles to vision and action lines.

- In line with the previous comment, the ‘Guiding Principles’ as they are currently presented seem to be a selection. Moreover, it is not well motivated why especially this set of principles is chosen. This should be explained/justified more. Now section 1.1.1 works as a perfect hook, but the following section(s) are not using that hook sufficiently.

- We suggest adding a glossary with definitions of the main concepts, to make the document more accessible to readers that are new to open science discussions. It will also help with the consistent use of definitions throughout the document (e.g. now confusion is created by using all kinds of alternatives to the ‘as open as’ adage).

Remarks on specific Guiding principles:

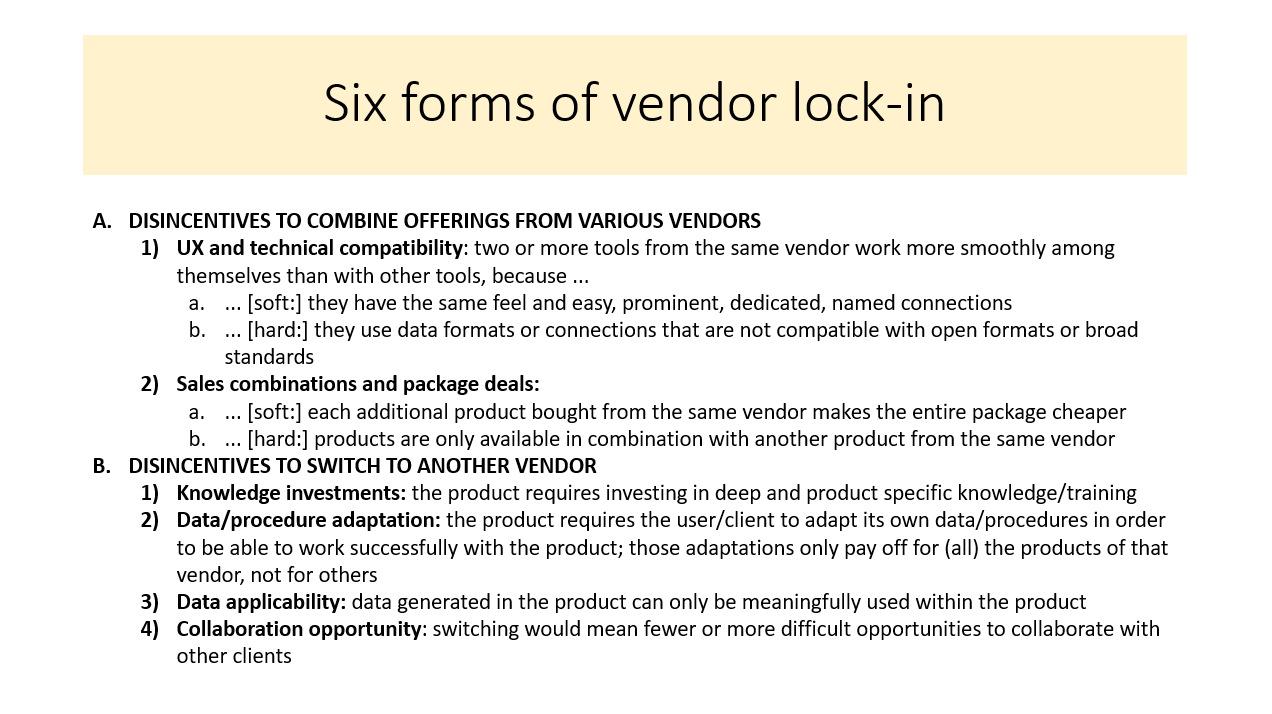

- The concepts of digital and academic sovereignty need much more explanation, especially as they are relatively new concepts and because they play an important role in various parts of the document. Also, it should be made more clear to what extent these are considered a driving force for open science (‘the interest of transparent, inclusive and reliable knowledge creation’) or, conversely, as a barrier to openness.

- The concept of subsidiarity also needs further clarification. It is implied that it will guide the process of the transition and which stakeholder will take up which role. It invokes the question of who this document is for. Is the document voicing the ambition of all stakeholders in NPOS? Also, the implications of this principle should be made more clear. What type of issues do require more national or centralized action even if that might deviate at some points from when and how all individual stakeholders would have acted (as for instance has been done in the case of national read and publish deals). The report mentions several instances of national initiatives, esp. for a number of platforms, OKB and such, as if decisions have already been taken. How does that fit into the subsidiarity principle?

Part 2: NPOS Vision for 2030

- We miss a more elaborate and contextualised vision for those aspects in the ambition that are new compared to the previous programme. It should be made clear why aspects like citizen science, digital/academic sovereignty, and the ambition to look at public values and to become less dependent on (commercial) publishers are so important. It should be clear to the reader what would go wrong if these were not addressed in the ambition. That is the case as the document is now. We also miss reference to the latest version of the Guiding Principles on Management for Research Information and its recommendations.

- We appreciate the aspect of making open science normative, but would suggest to not only leave this as something for open science communities to address. There is a clear need for leadership and influential role models to explicitly state a preference for practicing open science and expecting it from others. These could be deans, prize winners, and others.

Part 3: Programme lines and requirements

- The justification for the programme lines should be made much more prominent. Further on in the document, it is stated that the three programme lines are not the only developments that are deemed important, but that these are the ones where central coordination is considered crucial. The question why this is crucial is unanswered. This should be made much more prominent as an explanation of the choices made for NPOS2030. Also the reason for disregarding other aspects of open science (Open Education, Research Integrity and Reproducibility of scientific results are mentioned) is not very strong. It is stated that these are either already being taken up or relatively new. In our view both do not justify leaving these aspects out

- The central role of recognition and rewards in the transition to open science should be mentioned early on in the document, and a justification given as to why it is not in itself considered part of NPOS2030. Currently, it is only explicitly linked to Open Access. Similarly, research integrity gets a mention in relation to the organization of publishing, but in the current ambition document it does not seem to be considered an integral aspect of open science.

- We support the suggestion for alternative programme lines as proposed by the Open Science Communities Netherlands in their feedback (available at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1B4XGJQQSGwvGy1LzevB6n2nUoHiB2qDz/ ).

- The programme line Citizen Science seems to take a specific view on the relation between Open Science, Citizen Science and RRI (Figure 3). The emphasis on these as separate developments with only limited overlap encourages compartmentalization, rather than considering open science as an integrated approach towards more relevant, robust and efficient research.

- The requirements are not well integrated with the rest of the document. In the introduction to the requirements, it is mentioned that ‘(…) the Programme Lines will address a set of essential requirements needed for this culture change‘ – but this is not reflected in the description of the programme lines themselves.

Part 4: Key lines of action for the programme lines:

We only highlight the most pressing issues here. We won’t go into specific details (issues around consistent use of definitions, terminology and (business) models, etc.)

Open Access

- The action line on applying open access to all output is great but there is not a beginning of ideas on how to realize that. Also it is unclear whether the 100% OA goal is also applied to all outputs.

- The importance of metadata is lacking in the mission and action lines for open access, though it is said to be part of the OA programme line. Explicit attention for metadata is important in relation to OA of all scholarly output, as well as openness of this metadata. It could be part of negotiations with publishers as well as a consideration in creating publishing infrastructure.

FAIR data

- We regret that there is no action line on increasing the amount of publicly shared research data sets. It is somewhat disappointing that there is no guidance or ambition on what is expected regarding making data open and open-licensed, beyond just making it FAIR. Additionally we regret that the adage ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary’ has been watered down to ‘Open as early as possible, and closed when necessary’. We welcome that early opening up is seen as important but would advise to maintain the gradual nature of closedness, as in the original adage. In that context the concept of protected sharing introduced in this ambition should be framed as a way to share data that would otherwise remain closed and not as an excuse to not share in a fully open manner in cases where that is perfectly viable.

Citizen science

- We suggest adding a few lines defining citizen science. Also it would help to make clear how citizen science and public engagement are related, but also how they are different concepts.

- Currently the Citizen Science sections feels not very well integrated with the other sections. We would welcome a vision on the relation between FAIR and open data, open access and citizen science.